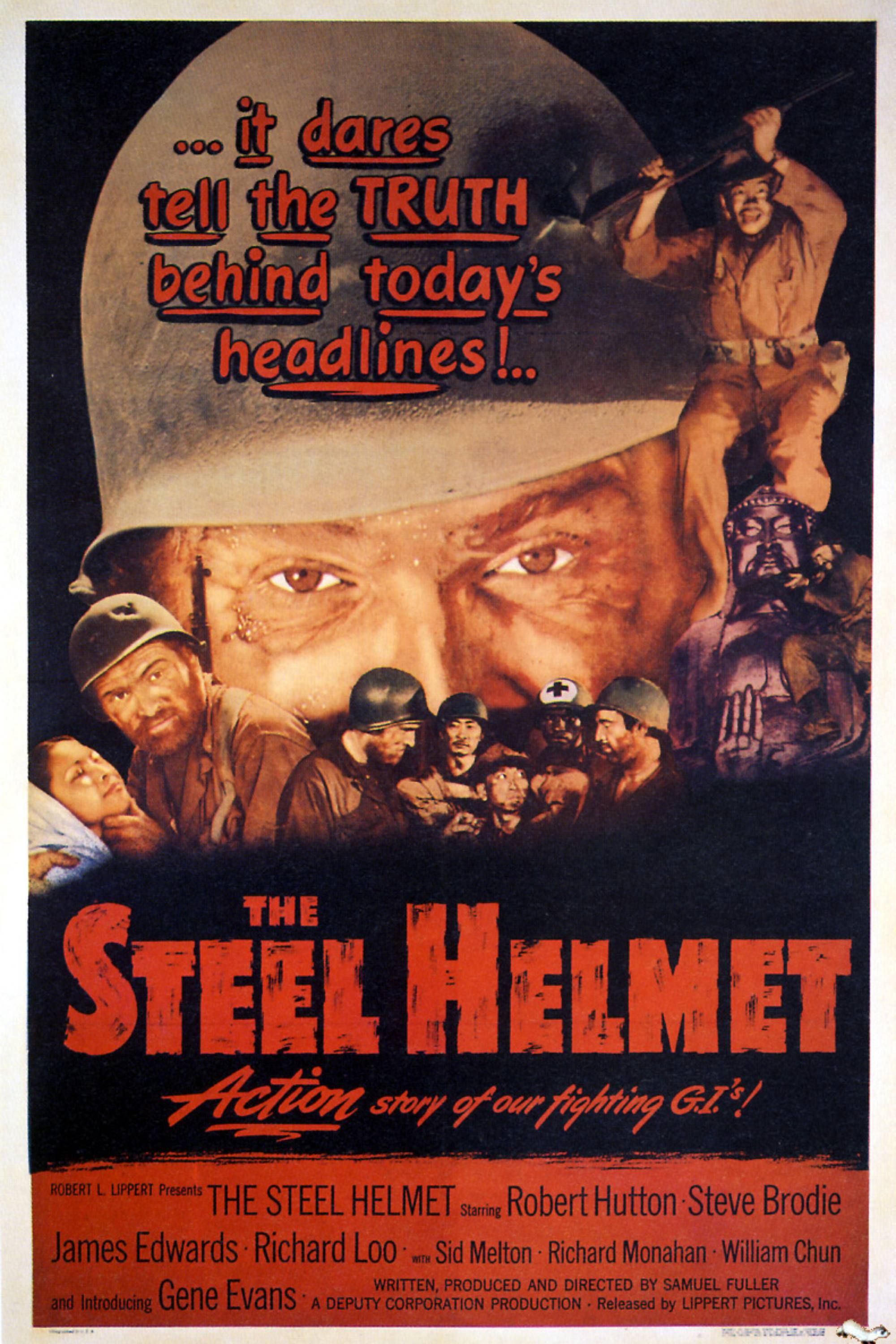

Samuel Fuller directed many war films throughout his long career, calling upon his own experiences during WWII to dramatize combat as realistically as possible. Although many of his subsequent war movies were more technically polished, few had the raw power of his first one: The Steel Helmet. Shot on a shoestring budget and cut together with stock footage, it was the first American feature centered on the Korean War, which had started in 1950. It could have easily faded into obscurity after hitting theaters in 1951, as more expensively mounted depictions of the conflict were released by major studios. Yet, The Steel Helmet remains a gritty, brutal portrayal of warfare that’s also a surprisingly ahead-of-its-time exploration of racism.

‘The Steel Helmet’ Makes the Most of Its Budget Limitations

Gene Evans plays Sergeant Zack, the sole survivor of a military unit that’s been wiped out in combat. He befriends an orphaned Korean boy who he nicknames Short Round (William Chun), and together they encounter Colonel Thompson (James Edwards), a Black army medic whose entire unit has also been slaughtered. The three join an integrated platoon led by Lieutenant Driscoll (Steve Brodie), who took charge after the ranking officers were killed. The platoon makes its way to a deserted Buddhist temple, where a North Korean soldier (Harold Fong) is also hiding out. After killing one of their men, the enemy solider, nicknamed The Red, tries to convert Thompson and Asian American Sergeant Tanaka (Richard Loo) to his side, questioning how either man can fight on behalf of the US. Their philosophical discussion is disrupted by an attack on the temple, during which Short Round and Lieutenant Driscoll are killed.

The Steel Helmet was Fuller’s third film as a director, following the low-budget Westerns I Shot Jesse James and The Baron of Arizona. It would be a similarly small-scale affair despite its grand ambitions. Rather than travel to location, Fuller and his team shot The Steel Helmet in Los Angeles’s Griffith Park, home to the famous observatory showcased in La La Land and Rebel Without a Cause. He worked quickly and cheaply, completing filming in just 10 days on a budget of $104,000 (less than the catering cost for most movies). Lacking the funds to recreate the climactic battle sequence, Fuller and his editors used stock footage instead.

Related

What’s the Truth Behind This Controversial Burt Reynolds Movie?

What happened in this sea-faring adventure movie is still a mystery.

Rather than being hindered by these budgetary restraints, Fuller plays into them. A former photojournalist and newspaperman, Fuller shoots The Steel Helmet with a you-are-there verisimilitude that stands in stark contrast to more Hollywood-ized dramatizations. His pseudo-documentary approach would soon become the norm for war movies like Saving Private Ryan and The Hurt Locker, which similarly try to place audiences in the war zone. Yet unlike those films, The Steel Helmet isn’t anchored by any recognizable stars like Tom Hanks or Jeremy Renner. Fuller’s cadets are all played by lesser-known character actors, adding to the feeling that you’re watching real soldiers as opposed to pretend ones.

‘The Steel Helmet’ Was Way Ahead of Its Time

Whether he was making a western, a noir, or a war film, Fuller never shied away from then-taboo topics his more respected contemporaries were too afraid to touch. He was particularly drawn to the issue of race, as seen in movies as varied as The Crimson Kimono, Shock Corridor, and White Dog. Made at a time when large portions of the United States were still segregated, The Steel Helmet faces the issue of American racism head-on in ways that are shockingly frank and contemporary. Sergeant Zack repeatedly refers to Short Round by a racial slur, only to see his humanity as their journey progresses. The North Korean soldier brings up Japanese Internment Camps and Jim Crow when asking how Black and Asian soldiers can defend a country that treats them as second-class citizens. The very nature of warfare itself is questioned, as a difference of ethnicity seems to be the only thing that distinguishes an enemy from an ally.

From his first war movie through his last, The Big Red One, Fuller views an Army platoon as the ultimate equalizer. No matter what the color of our skin, he argues, we all bleed the same shade of red. Perhaps if we understood that to begin with, we wouldn’t need to fight wars at all.

The Steel Helmet is currently available to stream on The Criterion Channel in the U.S.